By l_peer | July 25, 2013

Cross posted from ISPS Lux et Data Blog

These questions were on my mind as I was preparing to present a poster at the Open Repositories 2013 conference in Charlottetown, PEI earlier this month. The annual conference brings the digital repositories community together with stakeholders, such as researchers, librarians, publishers and others to address issues pertaining to “the entire lifecycle of information.” The conference theme this year, “Use, Reuse, Reproduce,” could not have been more relevant to the ISPS Data Archive. Two plenary sessions bookended the conference, both discussing the credibility crisis in science. In the opening session, Victoria Stodden set the stage with her talk about the central role of algorithms and code in the reproducibility and credibility of science. In the closing session, Jean-Claude Guédon made a compelling case that open repositories are vital to restoring quality in science.

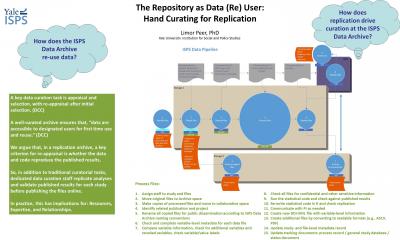

My poster, titled, “The Repository as Data (Re) User: Hand Curating for Replication,” illustrated the various data quality checks we undertake at the ISPS Data Archive. The ISPS Data Archive is a small archive, for a small and specialized community of researchers, containing mostly small data. We made a key decision early on to make it a “replication archive,” by which we mean a repository that holds data and code for the purpose of being used to replicate and verify published results.

The poster presents ISPS Data Archive’s answer to the questions of who is responsible for the quality of data and what that means: We think that repositories do have a responsibility to examine the data and code we receive for deposit before making the files public, and that this data review involves verifying and replicating the original research outputs. In practice, this means running the code against the data to validate published results. These steps in effect expand the role of the repository and more closely integrate it into the research process, with implications for resources, expertise, and relationships, which I will explain here.

First, a word about what data repositories usually do, the special obligations reproducibility imposes, and who is fulfilling them now. This ties in with a discussion of data quality, data review, and the role of repositories.

Data Curation and Data Quality

A well-curated data repository is more than a place to put data. The Digital Curation Center (DCC) explains that data curation means ensuring data are accessible to designated users for first time use and reuse. This involves a set of curatorial practices – maintaining, preserving and adding value to digital research data throughout its lifecycle – which reduces threat to the long-term research value of the data, minimizes the risk of its obsolescence, and enables sharing and further research. An example of a standard-setting curation process is the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). This process involves organizing, describing, cleaning, enhancing, and preserving data for public use and includes format conversions, reviewing the data for confidentiality issues, creating documentation and metadata records, and assigning digital object identifiers. Similar data curation activities take place at many data repositories and archives.

These activities are understood as essential for ensuring and enhancing data quality. Dryad, for example, states that its curatorial team “works to enforce quality control on existing content.” But there are many ways to assess the quality of data. One criterion is verity: Whether the data reflect actual facts, responses, observations or events. This is often assessed by the existence and completeness of metadata. The UK’s Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), for example, requests documentation of “the calibration of instruments, the collection of duplicate samples, data entry methods, data entry validation techniques, methods of transcription.” Another way to assess data quality is by its degree of openness. Shannon Bohle recently listed no less than eight different standards for assessing the quality of open data on this dimension. Others argue that data quality consists of a mix of technical and content criteria that all need to be taken into account. Wang & Strong’s 1996 article claims that, “high-quality data should be intrinsically good, contextually appropriate for the task, clearly represented, and accessible to the data consumer.” More recently, Kevin Ashley observed that quality standards may be at odds with each other. For example, some users may prize the completeness of the data while others their timeliness. These standards can go a long way toward ensuring that data are accurate, complete, and timely and that they are delivered in a way that maximizes their use and reuse.

Yet these procedures are “rather formal and do not guarantee the validity of the content of the dataset” (Doorn et al). Leaving aside the question of whether they are always adhered to, these quality standards are insufficient when viewed through the lens of “really reproducible research.” Reproducible science requires that data and code be made available alongside the results, to allow regeneration of the published results. For a replication archive, such as the ISPS Data Archive, the reproducibility standard is imperative.

Data Review

The imperative to provide data and code, however, only achieves the potential for verification of published results. It remains unclear as to how actual replication occurs. That’s where a comprehensive definition of the concept of “data review” can be useful: At ISPS, we understand data review to mean taking that extra step – examining the data and code received for deposit and verifying and replicating the original research outputs.

In a recent talk, Christine Borgman pointed out that most repositories and archives follow the letter, not the spirit, of the law. They take steps to share data, but they do not review the data. “Who certifies the data? Gives it some sort of imprimatur?” she asks. This theme resonated at Open Repositories. Stodden asked: “Who, if anyone, checks replication pre-publication?” Chuck Humphrey lamented the lack of an adequate data curation toolkit and best practices regarding the extent of data processing prior to ingest. And Guédon argued that repositories have a key role to play in bringing quality to the foreground in the management of science.

Stodden’s call for the provision of data and code underlying publication echoes Gary King’s 1995 definition of the “replication standard " as the provision of, “sufficient information… with which to understand, evaluate, and build upon a prior work if a third party could replicate the results without any additional information from the author.” Both call on the scientific community to take up replication for the good of science as a matter of course in their scientific work. However, both are vague as to how this can be accomplished. Stodden suggested at Open Repositories that this activity is community-dependent, often done by students or by other researchers continuing a project, and that community norms can be adjusted by rewarding high integrity, verifiable research. King, on the other hand, argues that “the replication standard does not actually require anyone to replicate the results of an article or book. It only requires sufficient information to be provided – in the article or book or in some other publicly accessible form – so that the results could in principle be replicated” (emphasis added in italics). Yet, if we care about data quality, reproducibility, and credibility, it seems to me that this is exactly the kind of review in which we should be engaging.

A quick survey of various stakeholders in the research data lifecycle reveals that data review of this sort is not widely practiced:

- Researchers, on the whole, do not do replication tests as part of their own work, or even as part of the peer review process. In the future, they may be incentives for researchers to do so, and post-publication crowd-sourced peer review in the mold of Wikipedia, as promoted by Edward Curry, may prove to be a successful model.

- Academic institutions, and their libraries, are increasingly involved in the data management process, but are not involved in replication as a matter of course (note some calls for libraries to take a more active role in this regard).

- Large or general data repositories like Dryad, FigShare, Dataverse, and ICPSR provide useful guidelines and support varying degrees of file inspection, as well as make it significantly easier to include materials alongside the data, but they do not replicate analyses for the purpose of validating published results. Efforts to encourage compliance with (some of) these standards (e.g., Data Seal of Approval) typically regard researchers responsible for data quality, and generally leave repositories to self-regulate.

- Innovative services, such as RunMyCode, offer a dissemination platform for the necessary pieces required to submit the research to scrutiny by fellow scientists, allowing researchers, editors, and referees to “replicate scientific results and to demonstrate their robustness.” RunMyCode is an excellent facilitator for people who wish to have their data and code validated; but it relies on crowd sourcing, and does not provide the service per se.

- Some argue that scholarly journals should take an active role in data review, but this view is controversial. A document produced by the British Library recently recommended that, “publishers should provide simple and, where appropriate, discipline-specific data review (technical and scientific) checklists as basic guidance for reviewers.” In some disciplines, reviewers do check the data. The F1000 group identifies the “complexity of the relationship between the data/article peer review conducted by our journal and the varying levels of data curation conducted by different data repositories.” The group provides detailed guidelines for authors on what is expected of them to submit and ensures that everything is submitted and all checklists are completed. It is not clear, however, if they themselves review the data to make sure it replicates results. Alan Dafoe, a political scientist at Yale, calls for better replication practices in political science. He places responsibility on authors to provide quality replication files, but then also suggests that journals encourage high standards for replication files and that they conduct a “replication audit” which will “evaluate the replicability and robustness of a random subset of publications from the journal.”

The ISPS Data Archive and Reproducible Research

This brings us to the ISPS Data Archive. As a small, on-the-ground, specialized data repository, we are dedicated to serious data review. All data and code – as well as all accompanying files – that are made public via the Archive are closely reviewed and adhere to standards of quality that include verity, openness, and replication. In practice it means that we have developed curatorial practices that include assessing whether the files underlying a published (or soon to be published) article, and provided by the researchers, actually reproduce the published results.

(http://isps.yale.edu/files/blog/Peer_OR2013poster_48x30_BlogVersion.pdf)

(http://isps.yale.edu/files/blog/Peer_OR2013poster_48x30_BlogVersion.pdf)

This requires significant investment in staffing, relationships, and resources. The ISPS Data Archive staff has data management and archival skills, as well as domain and statistical expertise. We invest in relationships with researchers and learn about their research interests and methods to facilitate communication and trust. All this requires the right combination of domain, technical and interpersonal skills as well as more time, which translates into higher costs.

How do we justify this investment? Broadly speaking, we believe that stewardship of data in the context of “really reproducible research” dictates this type of data review. More specifically, we think this approach provides better quality, better science, and better service.

-

Better quality. By reviewing all data and code files and validating the published results, the ISPS Data Archive essentially certifies that all its research outputs are held to a high standard. Users are assured that code and data underlying publications are valid, accessible, and usable.

-

Better science. Organizing data around publications advances science because it helps root out error. “Without access to the data and computer code that underlie scientific discoveries, published findings are all but impossible to verify” (Stodden et al.) Joining the publication to the data and code combats the disaggregation of information in science associated with open access to data and to publications on the Web. In effect, the data review process is a first order data reuse case: The use of research data for research activity or purpose other than that for which it was intended. This places the Archive as an active partner in the scientific process as it performs a sort of “internal validity” check on the data and analysis (i.e., do these data and this code actually produce these results?).

It’s important to note that the ISPS Data Archive is not reviewing or assessing the quality of the research itself. It is not engaged in questions such as, was this the right analysis for this research question? Are there better data? Did the researchers correctly interpret the results? We consider this aspect of data review to be an “external validity” check and one which the Archive staff is not in a position to assess. This we leave to the scientific community and to peer review. Our focus is on verifying the results by replicating the analysis and on making the data and code usable and useful.

-

Better service. The ISPS Data Archive provides high level, boutique service to our researchers. We can think of a continuum of data curation that progresses from a basic level where data are accepted “as is” for the purpose of storage and discovery, to a higher level of curation which includes processing for preservation, improved usability, and compliance, to an even higher level of curation which also undertakes the verification of published results.

This model may not be applicable to other contexts. A larger lab, greater volume of research, or simply more data will require greater resources and may prove this level of curation untenable. Further, the reproducibility imperative does not neatly apply to more generalized data, or to data that is not tied to publications. Such data would be handled somewhat differently, possibly with less labor-intensive processes. ISPS will need to consider accommodating such scenarios and the trade-offs a more flexible approach no doubt involves.

For those of us who care about research data sharing and preservation, the recent interest in the idea of a “data review” is a very good sign. We are a long way from having all the policies, technologies, and long-term models figured out. But a conversation about reviewing the data we put in repositories is a sign of maturity in the scholarly community – a recognition that simply sharing data is necessary, but not sufficient, when held up to the standards of reproducible research.